Ever wake up one day and realise your life means a whole lot less than you think it does? Look yourself in the mirror and realise that the world wouldn’t change a bit without you. Decide there’s not much point to anything you’ve done. That’s me. Meeting kids in a war zone will do that to you.

One week prior I considered myself a humble big-shot. Embarrassing to even write. The next moment I was shrinking inside a Jerusalem bar, trying to figure out how to hide behind a snooker cue. The first guy I met was a German bloke with a pencil-thin moustache and a flat-head, wrinkled cargo pants snapped onto his legs. He was a soldier carrying the shame of a nation on his back, completing his pilgrimage to Nazareth. He had a laidback smile that made you like him instantly and wore it like it was easy.

I wore my own smile constructed around who I thought I was. I was my work and had no shame about wrapping my entire identity around it. I’d made films that raised some eyebrows and that was enough for me. Deluded and tipsy, I thought I could change the world.

Military service is compulsory in Israel, in case you didn’t know—so every fresh faced youngster knows how to build and shoot an M16 assault rifle inside of three minutes. Makes you look at people different. The nineteen-year-old girl who was eyeing us up from across the bar was about to complete her tank demolition training, we found out. She had curly hair and green forget-me-not eyes, her mannerisms light and smiley, like she was in on some private joke none of us knew about.

I feel some obligation in saying that the year was 2019 and no real war was being fought back then. These kids were suspended between hypnotic propaganda from their superiors and post-teen excitement. They shot rifles and blew up clay compounds on the weekends. It’s easier to think you’re doing something noble when people aren’t dying around you. You can imagine that when they asked, ‘So, what do you do’ and I answered that I was a filmmaker, primarily in fashion and lifestyle, their eyes glazed over, a template smile welled up and they nodded politely. What I did was bullshit, b-o-r-i-n-g. I was pressing red buttons and following the swaying hips of models, they were walking away from orange explosions, Jason Bourne’s in the desert.

It wasn’t all country-loving demolition, though. The girl we played snooker against wore sex and rock n’ roll like it was perfume. She hated the army, the guns, the grown kids playing war in adult clothing. She shrugged about it like that’s the way things go, but she knew that what she did was badass. She was a sniper scout and even if she didn’t like it, she was damned good at it.

We smoked weed above Jerusalem streets, she, sketching the outline of my fading self in a leather-bound notebook, me, peering over the edge of the roof watching orthodox kids rush to synagogue. In the sunset, my occupation which I considered my—purpose—grew small and insignificant. I wasn’t deluded enough to believe that being a soldier meant making a difference, yet something about what was at stake paled in comparison to my personal pursuits.

‘Have you heard about the Messiah complex?’ She said, taking the joint back from me.

‘No,’ I said.

‘It’s this condition where people believe they’re the chosen one. They come to this city enamoured by the energy—it’s so dense here, you know?’

Every year around fifty cases pop up of lost travellers claiming to be the Messiah. In my own meandering search for purpose, I didn’t seem too far removed from religious vagabonds doing the same. Take a gifted individual with a large ego, politically disillusioned, with inflamed religious zeal who looks wide-eyed at Israel. They listen eagerly to the mythical tales. The end of times. The chosen land. The urgency in it all. The smoke clears and hey-ho, there you go, the Messiah complex. Of course, I didn’t believe I was the saviour. But in the modern world, where ‘God has died,’1 we’ve become our own Gods. We worship who we could be, who we can become.

The most desired job in today’s world is an influencer. Who is the Messiah but the ultimate influencer?

Despite the religious obsession which defined this city, for better or for worse, her eyes lit up when she spoke about sinning. Underground raves. A party turned sour after locals, dancing on LSD in the Negev desert, discovered a body in the trunk of a car. A man became a corpse in the desert heat, from dehydration, or asphyxiation, or some mixture of the two. I don’t know what I expected from a nineteen-year-old sniper who hated guns and loved dance music, but this wasn’t it. I turned my head sideways as she told me the story, romanticising idyllic fallacies about her.

I remember sitting in the hostel the day after feeling limp, unimportant, irrelevant. You pretend that what you do matters until you meet the layered life of someone misunderstood. Suddenly, your own dimensionality shallows in comparison.

I’d be lying if I said I figured it out since then. I didn’t change professions, become a doctor, or start a charity so I could, ‘make a difference.’ The experience left me with more questions than answers. I just kept on going. I forgot a lot of it, to be honest. Most people with the Messiah complex are healed after a few weeks outside the Holy Land.

I suppose I sobered up to the reality of my own self-importance. The world doesn’t revolve around me—shock, horror! But despite everything, there is something I can control, the way I show up, the way I interact with others. I learnt a valuable lesson. For things to mean something, you have to risk losing something, first. I don’t want to risk my life to complete the plan of politicians, but I do want to risk more of myself in the art I create. I want to put more on the line. I’m no saviour, I don’t pretend to be. But perhaps, the reward of doing good work, honest work, is saviour enough.

-IL.

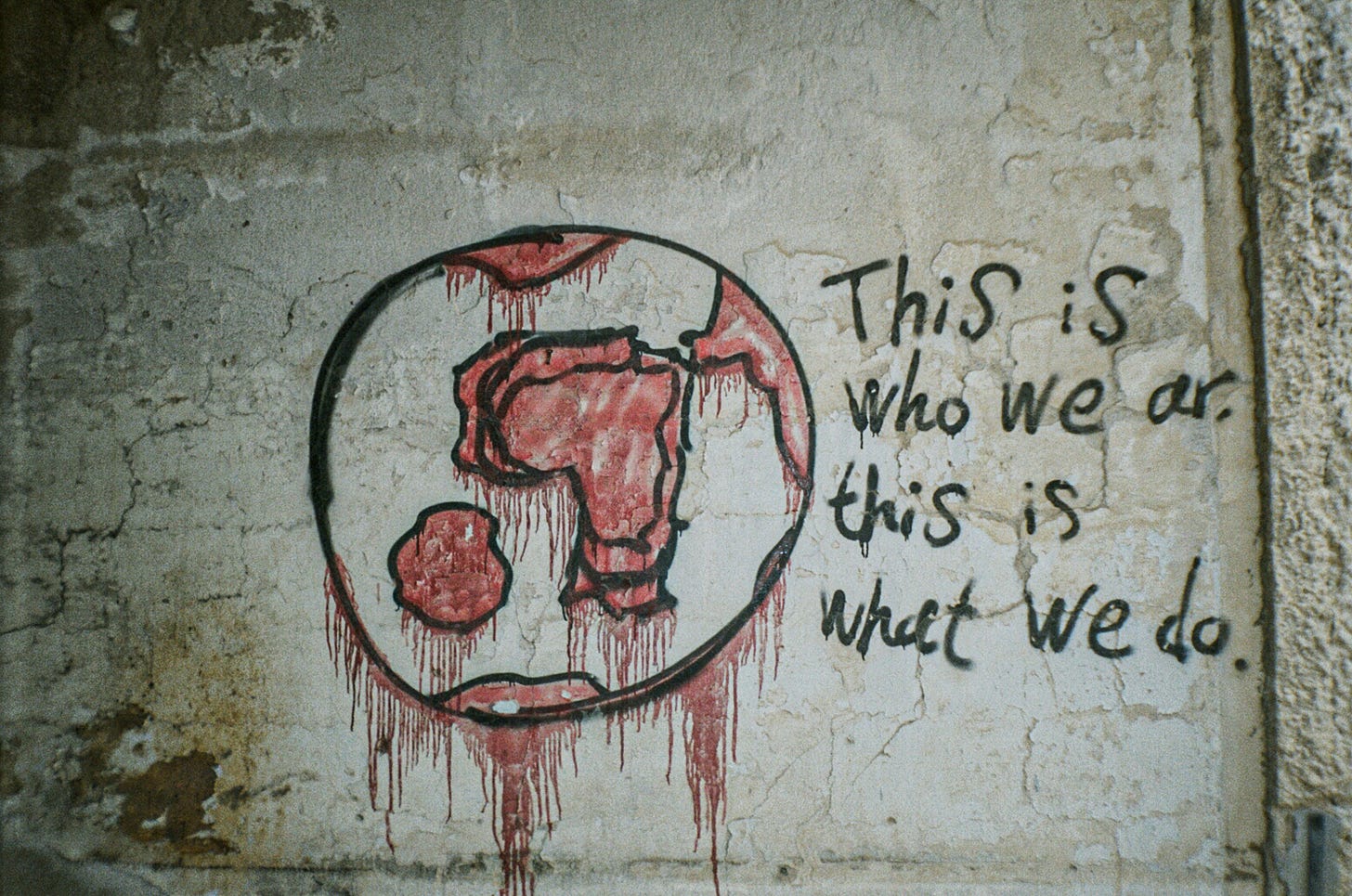

Images shot by IL.

Based on Nietzsche’s idea. Without a deity dictating meaning, we become responsible for our own values. This is both liberating and terrifying. We no longer have divine authority to tell us what to worship, so we begin to idolise potential—who we could be.

You give meaning to many; your purpose is significant through your creations and sharing your thoughts

Great read, really helps put my own preconceived notions of "purpose" into perspective.