Welcome to Bluezone. Every week, I send out weekly articles, explorations of creative philosophy and musings on things I discover. If you enjoy this, feel free to give it a like.

The cousin we don’t speak to anymore took me aside after my Bar Mitzvah into a darkened crook between two rooms. She handed me a gift in private, a rectangular object wrapped in coloured parchment, the smell of marijuana on her breath. She lit up the remnants of her joint and told me, ‘When I was your age, I read this, and it changed my life.’ I tore the wrapper off to reveal a cover of ‘The Catcher In The Rye.’ My lips formed into a polite smile; I hugged her.

Unbeknownst to me at the time, tales of existential adulthood were like a shadow that had not yet shaped itself beneath my form. When I finally read and re-read the book some years later, several moments stuck to my psyche like moisture to a car window. The moment when Phoebe, Holden Caulfield’s little sister, asks him what he wants to be when he grows up is an image drawn from idealistic ignorance, a beautiful yet tragic fallacy of good-natured futility.

“I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff—I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be.”

— J.D. Salinger

To be the catcher in the rye means to protect children from the unavoidable fate of adulthood, the hardening suffering we all avoid yet inevitably face in the rhythms of material existence. In the good-intentioned heart of a kid like Holden, we recognise the battle between ripening age and the self-preservation we cling to for the notion of an idealistic youth. And yet, there is a beauty to his false ignorance. Perhaps there is a beauty to ignorance itself. As I get older, I find myself looking at naïveté for its crystal clear simplicity, for its ability to coax courage out of us, for being a catalyst to growth. It allows access to a purity of experience that becomes harder to recapture once we know too much.

As adults, it’s easy to pretend to know more than we truly do. Just because we’ve seen decades pass, we believe we can anticipate, with more accuracy, the approaching winters, springs or summers that grace our lifetime. It’s a defence mechanism, and yet— so much of life is hidden beneath the folds that believing we truly know what’s going on and who we are is a hindrance to experiencing life in all its fullness. At different hours, we represent each of several of our ancestors, as if there were seven or eight of us rolled up in our skin. In the right light, a change of expression on the face of a friend reveals their mother or father in the window of their eyes, a hidden passenger in their facial angle, complexion, or depth of their pupil. To outsiders, we appear like a mosaic of lineage, history, and influence, far more than what we perceive ourselves to be. In our own eyes, we reduce ourselves to an amalgamation of occupations, passions, shortcomings, and strengths. To transcend beyond the labels, we must let go of what no longer serves us—both consciously and unconsciously— to rediscover the clarity of a childlike mind.

Developing positive ignorance means unlearning. Observing the world in a more 2D form as opposed to its 4D complexity. You don’t have to see this as stupefying yourself rather than another tool in the artistic armoury which simplifies. Cultivating intentional ignorance lets us look at the world not for what is necessarily real but for what is true. It can refresh us like the most soothing shower and bring us to heights we never dared to scale before. It keeps us young. To practice intentional ignorance, exercise the following habits.

Practice delusion

If you have a wildly ambitious goal and achieve it, you will be called a visionary. If you don’t, you will be labelled as having delusions of grandeur.

The common denominator here is, of course, delusion itself, and when practised with intentionality, it is like a prisoner experiencing freedom behind the bars of his cell.

Whilst it may not be true in the moment, the imagination can concoct a version of reality that gets reflected in our physiology and, therefore, begins to turn the alchemical cogs to transform the abstract into the physical.

We all need a dash of delusion.

How else can we have the faith to bring our ideas to life?

Next time a negative thought enters your mind, practice positive delusion. Tell yourself life will get irrationally better for no other reason than the secret to it becoming so is believing that it will.Be around young people.

Young people carry ignorance with them the same way birds carry wings.

It’s attached to them and, to the well-organised mind, there is much value to be drawn from such disposition.

To be around young people and to remain in their state of innocence can more easily allow us to experience intentional ignorance.

The key here is to hold your tongue.

To not get ahead of yourself with thoughts about consequences and rather to lose yourself in the passion of what lies in front of you.

After some time, the buzzing energy of ignorance rubs off, and we carry some of our idealistic hopefulness into our own lives.Talk to strangers

The beauty of talking to strangers lies in the fact that you will most probably never see each other again after the interaction.

This means divulging even your darkest of secrets has little consequence on the social dynamic of your friend group.

We can let our guard down and talk with earnestness, knowing that our truth won’t travel past the moment of conversation.

We are but passing shadows to each other, and so, much can be let go in the wind.

The key to talking to strangers is to remain curious, first and foremost, to be open in your approach and, if it helps, to mix false stories in with the true ones like a game of theatre.

They don’t know you or anything about you, and therefore you can be anyone.

It is not always important to be real in such cases as much as it’s important to be true.Ask for feedback and ignore the words

When asking for criticism on a piece of work you have created, it is less helpful to listen to the words of the critic than it is to observe their physicality and body language.

To neglect the verbal response and focus instead on the physicality allows us to follow the whispers of our intuition and tap into what lies unsaid.

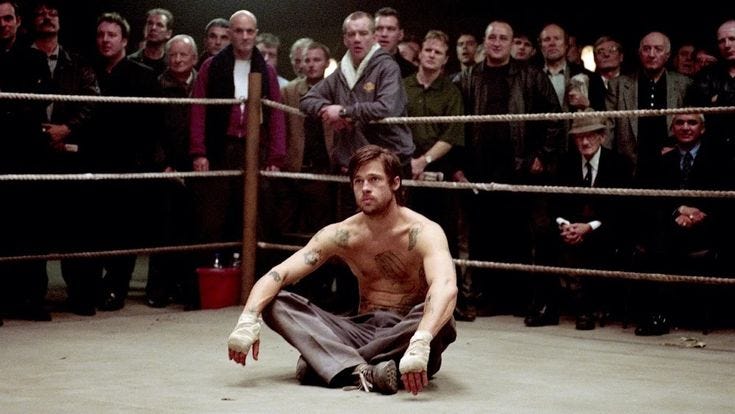

Much of intentional ignorance relies on interacting with feeling as opposed to rationality.Try to fail

Sometimes, the greatest way to achieve success is to permit ourselves to fail spectacularly at first.

If we feel stuck in a piece of work, even though we know what to do, it can be helpful to do the complete opposite.

It will probably be terrible.

It will probably create the most undesirable of results, and yet, it will unshackle the performance anxiety that is pent up in us ambitious folk.

When we have worked the failure out of our system, the original plan of action will feel free and fresh in its lightness.

Try to fail so you can succeed.

Intentional Ignorance, then, is not the absence of knowledge but a gateway to a purer form of living. It allows us to approach the world with fresh eyes, free from the weight of over-analysis and expectation. In the same way a child plays unburdened by the complexities of what they "should" know, we, too, can learn to embrace that clarity of presence. In the act of shedding unnecessary knowledge, we make room for creativity, intuition, and the kind of resilience that can only be forged through simplicity.

As we navigate the increasingly complex landscape of adulthood, it is easy to become overwhelmed by the need to understand everything—to seek certainty and control. But perhaps, in doing so, we lose the very essence of what makes us human: the ability to wonder, to explore, to be open to the unknown. By cultivating a kind of intentional ignorance—letting go of the need to know everything—we create space for the imagination to roam freely, for life to unfold with all its mysteries intact.

True wisdom may not always lie in knowing more— in fact, it may equally lie in knowing what to forget. By cultivating intentional ignorance, I hope that we can return to a place of curiosity and discover the courage to create alongside the resilience to face whatever comes next.

Wonderful as ever. On the topic of feedback, I used to say to my teams, the fastest way to disappoint a client is to do what they say, don’t listen to what they say, simply feel what they want and do that. Also when working with a client we always pushed 2 steps further than the brief, so when getting client feedback on the work, the choice is yours to how you walk away from the experience. Acknowledge that you will always have to take a step back on the project after feedback, but that still leaves one step forward left, it up to you which you focus on the step you had to take back or the step you moved them forward that was left. 2 steps forward, then one step back, is still moving your client forward, focus on that triumph of consistent forward motion. Cheers, Lauren

This is very insightful, thank you!